Information and Coding Theory (ICT Part 1)

Introduction

What is Information Theory:

Information theory answers two fundamental questions in communication theory: What is the ultimate data compression (answer: the entropy ), and what is the ultimate transmission rate of communication (answer: the channel capacity ).

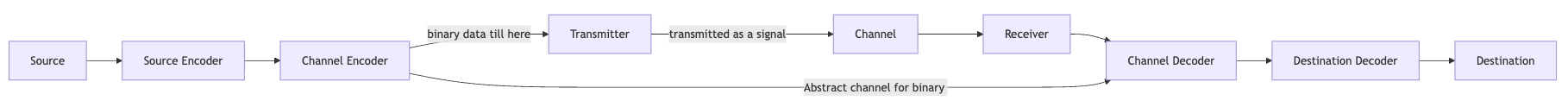

Data transmission at the physical layer:

Data Compression:

Data compression is done by the source encoder. Well-defined data sets such as the english alphabet, images, and audio need to be converted into bit strings before being modulated into signal form by the transmitter. Data compression achieves this through lossless (no information is lost) or lossy (information is lost) compression.

Transmitter:

Converts the binary data from the physical layer to a signal.

Erroneous Channel:

The transmission channel is erroneous and can result in bit flipping in the received data.

Channel Encoder:

Modifies the binary data such that the channel decoder can recover error less data; this is done by appending a redundancy code to the data. Error detection can be done using cyclic redundancy codes (CRC) and error correction can be done using stop-and-window.

Adding redundancy codes will occupy the channel transmission rate that could have been utilised by the encoded source data. We want an optimal rate (which depends on the channel) for transmitting the data with error correcting codes.

The entropy of the source gives a lower bound on how much data compression we can apply to make the channel communication optimal.

Hence, compression has two metrics:

- Compression ratio

- Resulting transmission speed

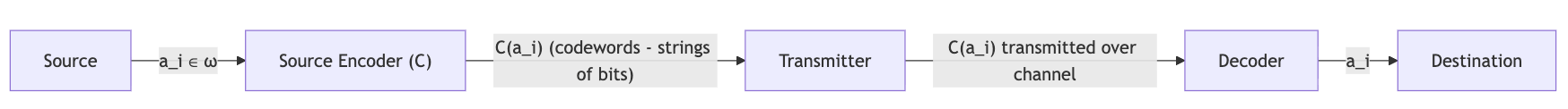

Source Encoding

Data Compression

The information at the source can be in any form (even non-binary), but the source encoder should convert it to binary form as binary is well suited to be converted to signal form.

is the alphabet of the source. We assume it to be a finite set (infinite sets are dealt with in a different way). For example

Source encoding function:

maps a single alphabet () to a binary string

maps a finite length string with .

The (1) requirement for is that should be injective. If is injective then is non-singular (same for ).

The (2) requirement for is that is a set of codes .

Assuming a defined we will interchangebly call as a code sometimes.

For example, (concatenated)

Example 1:

defined as:

Problem: this cannot be decoded correctly, as , , and .

Hence, we get to the requirement (3) should be injective.

(4) An encoder is called uniquely decodable if is non-singular.

Now we can fix the problem we faced earlier, but will the decoding be efficient?

Example 2:

Here, we consider the case that is uniquely decodable.

If we get a , we check if we have odd number of following s or even. Even number of s would result in the decoding and odd number of s would result in the decoding .

Problem: In the worst case, we will have to read the entire string to determine the parity of bits.

-> One possible fix could be to demarcate the string as and get a uniquely decodable without requiring to be non-singular; however, this will occupy a lot of extra bits post encoding which can grow in the size of the length of the string.

Following on this problem, we arrive at the requirment (5) for .

(5) should be prefix-free. That is, no codeword should be extendable to another codeword

is prefix-free if for for no such that .

Prefix-free Uniquely decodable Non-Singular Set of all codes;